Therapy

Once liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma: HCC) has been diagnosed, spread (metastases) have to be searched for. Then the doctor and patient make a joint decision about the treatment (therapy) to be performed.

Specific treatment methods for liver cancer are:

- Surgery (partial liver resection or liver transplantation)

- Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) or acetic acid injection (PAI)

- Radiofrequency-induced thermoablation (RFTA, RITA, RFA)

- Transarterial (chemo-)embolization (TAE, TACE)

- Transarterial radioembolization (TARE) or selective internal radiotherapy ( SIRT)

- External radiotherapy

- Drug therapy with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib

- Cytoreductive chemotherapy

or a combination of these treatment modalities.

What therapy is applied in a particular patient depends on the degree of disease progression at the time of diagnosis and on liver function. The patient’s age and general state of health are also considered when choosing the treatment method.

The most important surgical procedures for treating liver cancer are partial liver resection or complete removal of the liver followed by transplantation. However, the latter can rarely be performed (in less than five percent of patients). The aim of surgery is to completely remove the tumor in order to cure the disease. Partial liver resection is only possible, however, as long as the tumor is confined to the liver and can be removed with an adequate margin of healthy tissue. Moreover, partial liver resection must not jeopardize liver function. Thus resection may not be possible with severe portal hypertension or too small liver remnant

In more than three quarters of all cases, liver cancers are diagnosed too late to be surgically removed. Local ablation (tumor-destroying) procedures are used as an alternative to surgery but also as a bridge to transplantation. The ablation procedures include ethanol injection and radiofrequency-induced thermoablation. At least for small tumors (up to 3 cm in diameter), radiofrequency ablation is comparable to partial liver resection with regard to effectiveness and prolongation of life. HCC disease can be cured in this way.

Treatment approaches for liver cancer that cannot be completely removed or destroyed by either surgery or local ablation include transarterial (chemo- or radio-) embolization and/or drug therapy. Medical therapy with the drug sorafenib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, cannot cure advanced liver cancer. However, sorafenib can stop the growth of the tumor for a certain period of time, relieve tumor-related symptoms and prolong survival.

Surgery / Liver transplantation

The decision in favor of surgical resection or liver transplantation depends particularly on whether or not the tumor is accompanied by cirrhosis (“liver shrinkage”).

Surgical resection of the tumor is the treatment of choice for liver cancer without underlying cirrhosis. The aim is to completely remove the tumor and thus to cure the disease. This can be best achieved if the tumor is detected early and can be removed with a safety margin of normal tissue. So the surgeon removes not only the tumor itself but also some healthy tissue beyond its borders. This is done to ensure that the liver harbors no residual tumor cells.

Once cirrhosis develops, it is often too late for this type of surgery because not enough liver tissue would be left to maintain sufficient liver function. Thus liver function should always be checked by an interdisciplinary team before surgery. The surgeon and the oncologist should consult with the hepatologist, a liver expert, in this matter.

If the patient also suffers from cirrhosis, the preferred treatment for an early-stage tumor is complete removal of the liver followed by transplantation. This eliminates not only the liver tumor but also the underlying liver disease. However, transplantation can only be performed in a small number of patients. Prerequisites include the following: the tumor must be confined to the liver, and there must be no metastases (for example, in the lymph nodes). If transplantation is out of the question, the doctor will determine whether the tumor can still be surgically removed. The usefulness of surgically resecting the liver cancer depends on the size and location of the tumor, the liver function, the presence of portal hypertension, and the patient’s general condition. In selected patients with good liver function (Child-Pugh A) and a small singular HCC, the 5-year survival after liver resection is comparable to that after liver transplantation.

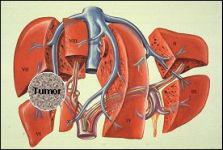

Fig. 7: Surgery of hepatocellular cancer

Modified from Scherübl et al., Patientenbroschüre Falkfoundation 2012

Radiofrequency-induced thermoablation

Radiofrequency-induced thermoablation (RFA; RFTA, RITA) is performed by inserting a probe into the liver tumor under ultrasound or CT guidance. Radiofrequency waves are sent through this probe to generate heat in the tumor tissue. Tumors with a diameter up of 3-5 cm can literally be “boiled” by using this method. The treatment is usually carried out in one to two sessions under short-term anesthesia.

Numerous studies have verified the effectiveness of local ablation (tumor-destroying) procedures for liver cancers up to 3-5 cm in diameter. The treatment has proven to be well tolerated. RFTA is just as effective as partial liver resection for tumors with a diameter of up to 3 cm. Comparative prospective studies have shown no difference in survival times between RFTA and liver resection in small (<3 cm) liver cancers. Patients with a single tumor and good liver function have the best chances of success.

Laser-induced thermotherapy and cryotherapy are also well-established, local ablation procedures, though used far less often than radiofrequency-induced thermoablation.

Local ablation procedures do not preclude liver surgery at a later date. In many cases, they even serve as a bridge to liver transplantation. Today, they are increasingly used in combination with drug treatment (sorafenib) or with transarterial (chemo-) embolization. The combined treatment approach is known as multimodal therapy. Early clinical studies hint to a survival advantage of multimodal therapy over sorafenib monotherapy in patients with advanced liver cancer.

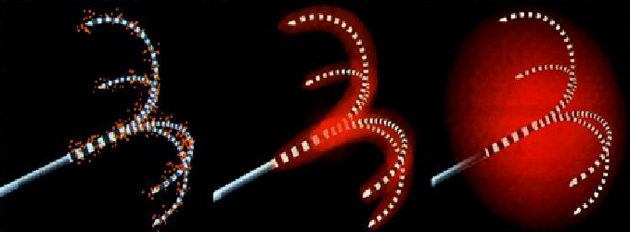

Fig. 8: Radiofrequency-induced thermoablation of hepatocellular cancer: The probe is inserted into the tumor. Radiofrequency waves are sent through the probe to generate heat in the tumor tissue. Temperatures between 50-120°C are obtained in the lesion and the tumor is destroyed.

Modified from Scherübl et al., Patientenbroschüre Falkfoundation 2012

Local treatment methods

Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI)

Percutaneous ethanol injection involves injecting 95% alcohol into the tumor with a fine needle under ultrasound or CT guidance. This destroys the liver tumor with minimal damage to the surrounding normal liver tissue. The treatment is usually performed in several sessions scheduled two to four weeks apart. It often has to be repeated after some months. Ethanol can be substituted by acetic acid. This treatment can potentially cure the disease.

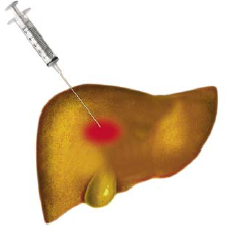

Fig. 9: Local destroyal of tumor (local ablation) by ethanol: The injection of ethanol (95%) into HCC (red) is depicted.

Modified from Scherübl et al., Patientenbroschüre Falkfoundation 2012

Transarterial (chemo-) embolization (TAE, TACE)

Transarterial chemoembolization is a local treatment procedure combining embolization with chemotherapy. After local anesthesia, the interventional radiologist advances a catheter from the groin into the hepatic artery. The hepatic artery branches out into small arteries in the liver. A liver tumor receives its blood supply from one or more of these small arteries. Embolization involves injecting very small plastic particles through the catheter into the tumor-supplying vessel until they block the vessel and stop the blood supply to the tumor. Nutrient and oxygen deprivation causes the tumor cells to die. The procedure is referred to as chemoembolization if a chemotherapeutic agent is also injected through the catheter and thus delivered directly to the tumor (“local chemotherapy”). The chemotherapeutic agent also induces cancer cell death. Transarterial embolization and transarterial chemoembolization are currently considered to be equally effective (in HCC).

(Chemo-) embolization is not used for early-stage liver cancer. Early-stage HCC is best treated with radiofrequency ablation, liver resection or even transplantation. (Chemo-) embolization is mainly used to treat large and multifocal tumors that cannot be surgically removed or treated by local ablation. It can delay tumor growth but should only be performed in patients with good liver function. In recent years, (chemo-) embolization has also been used as a bridge to liver transplantation and is now increasingly being combined with drug therapy (sorafenib) and local ablation procedures (e.g., radiofrequency-induced thermotherapy). The concept of multimodal therapy is becoming established.

Fig. 10: Transarterial (chemo-) embolisation of hepatocellular cancer (HCC). On the left HCC is shown before, and on the right after successful embolisation.

Modified from Wagner et al., 2006

Transarterial radioembolization (TARE)

A new procedure holds promise for patients with liver-confined HCC that cannot be treated by surgery or local ablation: transarterial radioembolization (TARE), often also called selective internal radiotherapy (SIRT). TARE (SIRT) is a new type of local radiation therapy that destroys liver tumors from the inside.

In this procedure, microspheres containing radioactive material with very short-range emissions are introduced directly into the vessels supplying the liver. Microsphere-encapsulated 90-yttrium, a so-called beta emitter, is injected directly into the hepatic artery through a catheter inserted in the patient’s groin under local anesthesia. The tumors are thus exposed to a high local radiation dose, and, at the same time, the tumor-supplying vessels are occluded. Delivering radioactivity to the hepatic artery or its branches with pinpoint accuracy is decisive, because the flow of radioactive microspheres into other abdominal blood vessels can cause considerable side effects.

In recent years, transarterial radioembolization (TARE) has gained a foothold in the treatment of liver cancers. The advantage of TARE over transarterial chemoembolization lies in the fact that it is usually performed in a single session, i.e. during a single hospitalization, and can also be used in patients with portal vein occlusion. Due to its high costs, TARE has thus far only been available to selected patients at special centers. In future clinical trials, TARE will also be combined with other treatment procedures, particularly drug therapy (sorafenib).

So far there have been no controlled prospective studies comparing TARE with TACE/TAE. However, currently available data suggest that the two procedures (TARE and TACE) are equally effective in the treatment of liver cancer.

External radiotherapy

Radiation therapy applied to the body from the outside (external radiotherapy, conformal radiotherapy, stereotactic radiotherapy) plays an important role in the treatment of large locally confined liver cancers that cannot be destroyed by surgery or minimally invasive procedures. Stereotactic radiotherapy achieves high response rates; it is currently being further developed in the context of ongoing studies and is often combined with drug therapy.

Proton therapy

Proton therapy can target tumors more precisely than conventional radiotherapy. However, it has not yet been examined for hepatocellular carcinoma in controlled trials. Several small pilot studies have yielded encouraging results and justify pursuing this approach further.

Drug therapy with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib

Targeted drugs interfere with various signaling pathways of tumor metabolism and thus act specifically against malignant tissue. Drugs that specifically inhibit growth signals and growth factors have been used for some years to treat bowel, breast, prostate and lung cancer. In 2007, sorafenib became the first drug approved for treatment of liver cancer.

About seven out of ten patients already have advanced liver cancer at the time of diagnosis and can no longer be treated by surgical resection or local ablation of the tumor. Except in patients without cirrhosis, systemic chemotherapy is not very effective and offers no survival advantage. Treatment attempts with hormones or immunotherapies have also been disappointing so far.

New drugs that act at the molecular level have finally brought advancement to drug therapy of liver cancer (HCC). These innovative drugs are directed against one or more factors that promote the growth of liver cancer. Many hepatocellular carcinomas have a large number of receptors for such growth factors on the surface of their cells. Growth factors can directly act on tumor cells. The new targeted agents stop this by blocking growth factor receptors or growth signals transmitted into tumor cells. In this way, tumor growth can at least be temporarily arrested.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib

In recent years, two large international trials have consistently shown that sorafenib prolongs the survival of patients suffering from advanced liver cancer. It inhibits tyrosine kinase enzymes and thus delays the growth of tumor cells and the vessels supplying them. Sorafenib is the first and thus far only drug that has been proven (by two phase III clinical trials) to prolong the lives of patients with liver cancer. Investigations are now underway to examine whether sorafenib has a life-prolonging effect not only in patients with advanced liver cancer but also in those with earlier tumor stages.

First clinical trials indicate that multimodal treatment with sorafenib (+ a local ablation procedure) plus TAE/TACE is superior to sorafenib monotherapy in patients with advanced liver cancer. In current studies, sorafenib is being combined not only with transarterial chemoembolization and RFTA but also with transarterial radioembolization, external radiotherapy or liver resection. Apart from sorafenib, other targeted drugs (e.g., bevacizumab, erlotinib, cetuximab, lapatinib, and c-Met inhibitors) are currently being investigated for their effectiveness and safety in the treatment of liver cancer.

Recently the c-MET inhibitor tivantinib has demonstrated statistically significant improvements in time to progression and overall survival versus placebo among patients with unresectable HCC in a phase II trial, particularly those with high MET expression levels. Based on the data of this small phase II study, a large phase III trial is now being initiated.

Cytoreductive chemotherapy

Cytoreductive chemotherapy has no clinical relevance for HCC patients with advanced cirrhosis (Child-Pugh stage B or C). In Asia and Africa, however, many people with chronic hepatitis B infection develop hepatocellular carcinoma without liver cirrhosis. Various chemotherapy strategies have been investigated in this group of patients, including cisplatin+gemcitabine, cisplatin+interferon+doxorubicin+5-fluoruracil (5-FU), doxorubicin+cisplatin, doxorubicin monotherapy, capecitabine monotherapy as well as 5-FU plus oxaliplatin. The combination of 5-FU and oxaliplatin has gained a certain amount of clinical recognition in some Asian countries.

The cytostatic agent doxorubicin is particularly suitable for combination drug therapy with sorafenib. Thus, early clinical trials have shown that doxorubicin combined with sorafenib achieves better tumor control and longer survival than doxorubicin alone. Controlled phase III trials are currently underway to confirm these results again with a sorafenib control arm.

Current clinical trials are also examining sorafenib in combination with cytoreductive agents such as oxaliplatin, capecitabine, 5-FU or doxorubicin.

Pain treatment

Pain that can considerably diminish the quality of life is often the main concern of patients with advanced cancer. One of the most important measures is effective pain management. The available drugs and methods usually provide effective relief of cancer pain. Treatment with painkillers, including morphine, is of the utmost importance. Pain treatment is tailored to the patient’s individual situation. Outpatient pain clinics and palliative (home)care services provided by many hospitals have particularly competent specialists in this field.

Contact

Center of Interventional Hepatobiliary Medicine

Prof. Dr. med. Hans Scherübl

Vivantes Klinikum Am Urban

Academic Teaching Hospital of Charité, Berlin

Dieffenbachstraße 1

10967 Berlin

Tel: + 49 30 130 225201

Fax: + 49 30 130 225205

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

vivantes.de/kau/gastro/